Brisbane Stadium Analysis

In a world where technology is evolving at lightning speed, the way we experience live sport is changing too. Television revolutionised access to major sporting events in the 20th century and we’re now on the brink of another major shift: the rise of Virtual Reality (VR) and immersive broadcast technologies. These tools have the potential to deliver front-row experiences to millions of people without the need to leave their homes, offering new possibilities for fan engagement, accessibility and sustainability.

Sporting authorities across Europe and the United States increasingly caution against building oversized, underused stadiums that become economic liabilities. The global trend is shifting toward smaller, smarter venues - stadiums designed with flexible, modular seating and integrated technologies that enhance both in-person and remote viewing experiences. With advances in Virtual Reality and immersive broadcast technology, fans can now enjoy front-row experiences without needing to be on-site. Rather than relying solely on large-scale venues, some technology companies are exploring boutique-style spaces specifically designed for shared VR sports viewing, bringing people together in smaller settings without the immense cost and footprint of traditional stadiums. It’s a forward-looking model that prioritises accessibility, sustainability and economic responsibility over outdated “bigger is better” thinking.

In the United States, new stadium projects are often smaller in capacity but feature premium experiences such as high-end hospitality and lounges. These aim to keep fans “in the moment” for longer and generate more revenue per attendee rather than relying on sheer numbers. Many stadiums are now being developed as mixed-use precincts (shopping, dining, entertainment) because the stadium alone is no longer a viable standalone business model. The focus is on quality over quantity: smaller capacities, better tech integration and sustainable economic models.

Reverse economies of scale mean that building “cheap” high seats in larger stadiums is not cost-effective. The higher up and further away the seats, the more expensive they are to construct, yet they generate less revenue because they’re considered the “cheap seats.” This undermines GIICA’s logic for a mega-stadium.

Many Australian stadiums are already too large for the sports they host, leading to the sight of empty seats at games, which negatively impacts the atmosphere, fan experience and broadcast appeal. Sports like cricket and AFL often struggle to fill mega-venues outside of marquee matches, raising questions about the economic justification for building bigger stadiums. Empty seats are not just a bad look but also represent lost revenue and underutilised infrastructure. Smaller, well-designed stadiums often create a better fan experience and are cheaper to maintain. They also better match the actual attendance patterns of local sports. Stadium projects should be built with realistic audience demand in mind, rather than chasing prestige or trying to replicate models from larger cities like Melbourne.

“A major dilemma in Australia has been the large disparity in average live attendance between the most active stadium builder, the AFL, and other sports sharing the venues for which they have expertly garnered taxpayer funding.”

- Richard Hinds, “When our stadiums are oversized, the atmosphere and intimacy of the game suffers”

This world-wide sporting trend directly challenges one of GIICA’s main criteria for selecting a stadium venue - that Brisbane needs a 60,000-65,000 seat stadium.

Round vs Rectangular Stadiums

In assessing stadium needs for Brisbane, it’s important to recognise the difference between round and rectangular venues. The Gabba, a round stadium, is suited primarily to cricket and AFL and hosts very few major non-sporting events - historically, only about one major concert per decade. In contrast, Suncorp Stadium, Brisbane’s largest rectangular venue, is a genuine multi-use facility. It regularly hosts Rugby League, the city’s most popular sport, including the Brisbane Broncos and State of Origin matches, as well as international Rugby Union, soccer and a steady calendar of concerts and entertainment events. This versatility delivers significantly higher utilisation, broader community benefit and stronger economic returns than a single-sport-focused round stadium.

Historic AFL & Cricket Attendance

The primary tenants of the Gabba stadium are Queensland Cricket and the Brisbane Lions. GIICA recommended a stadium in Brisbane with a 60,000 - 65,000 seat capacity to support AFL and cricket usage. However, these figures would appear to be highly inflated projections when looking at historical attendance figures for AFL and Cricket at the Gabba.

While some AFL and cricket fans may call for a 80,000+ seat stadium to rival the MCG in Melbourne, the reality is that Brisbane’s sporting landscape is markedly different. Melbourne hosts six AFL teams, with four regularly playing at the MCG. Western Australia has 160,000 AFL members split across two AFL teams and both of these teams use Perth’s Optus Stadium. In contrast, Brisbane has only one team, the Brisbane Lions, and there is little indication that more than one additional team would be established in the city in the foreseeable future if any new teams are added at all. The case for Brisbane having a bigger oval stadium doesn’t stack up.

Although AFL generally attracts stronger crowds than cricket in Brisbane, attendance is closely tied to the team’s performance. When the Brisbane Lions are winning, crowds increase; when they’re not, attendance drops significantly. While it’s natural to hope for long-term success, it’s not realistic to assume one team can sustain premiership-level performance every year for the next three decades.

If we look at historic attendance for AFL games at the Gabba -

Gabba capacity for AFL is 37,000

In 2024, the average AFL attendance at the Gabba was 30,784

In 2024, eight games “sold out” in the season however a sell-out crowd equates to 30,000+, not necessarily the full stadium capacity

While the Brisbane Lions has a membership of 62,000 (as of early 2025), that does not directly equal game attendance

The following is a list of the largest stadiums in Oceania -

Challenging GIICA’s Capacity Analysis

In its 100-Day Review, GIICA presented the graph below, asserting that Queensland has the lowest provision of major sporting stadium seating capacity relative to population when compared to Australia’s five most populous states.

However, GIICA has not disclosed the methodology behind this analysis, such as how it defines a “major stadium” or whether it distinguishes between rectangular and oval venues. This lack of transparency raises significant questions about the validity of the comparison.

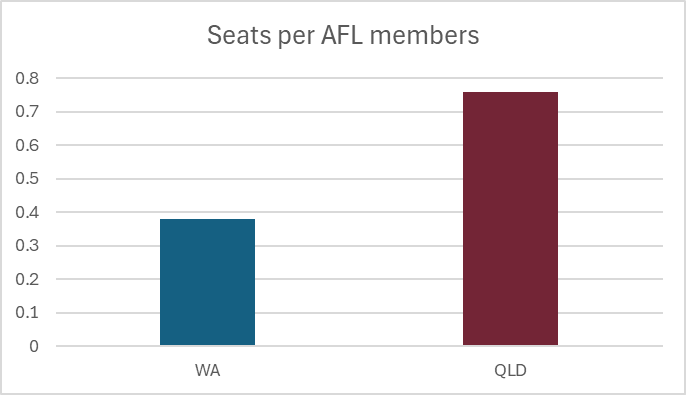

Queensland is Australia’s most decentralised state, which means its population is not as concentrated in one major city such as Victoria or New South Wales. Below is a different methodology, one among many, for assessing Queensland’s oval stadium capacity needs. This method looks at two of Australia’s mid-sized states - Western Australia and Queensland and considers two key factors only: the current oval stadium context and AFL membership numbers. For the purposes of this analysis, a major stadium is defined as 25,000+ seats.

Western Australia

AFL membership (Fremantle Dockers and West Coast Eagles): 160,000 combined

Major oval stadium capacity: 60,000 seats

Seating provision: 0.0375 seats per members

Queensland

AFL membership (Brisbane Lions and Gold Coast Suns): 91,000 combined

Major oval stadium capacity: 69,500 seats

Seating provision: 0.76 seats per member

This comparison highlights that Queensland AFL fans already have greater access to seating compared to their WA counterparts.

It is also critical to note that in January 2024, the AFL advised the 60-Day Olympic Sports Venue Review that its requirements for a main stadium in southeast Queensland were only 45,000–50,000 seats. GIICA has not justified why Brisbane requires an additional 13,000 oval stadium seats beyond what the AFL, the stadium’s primary tenant has said is necessary. It is possible that the Brisbane Lions may have shifted its position following their 2024 premiership win, but this logic is flimsy at best. Two premierships do not suddenly warrant a 60,000-65,000-seat venue that far exceeds both long-term demand and financial prudence.

Is a Smaller Stadium “Embarrassing” on the World Stage?

One of the recurring justifications for a 63,000-seat stadium is the idea that anything smaller would be “embarrassing” for a host city on the world stage. This is a vanity metric, not a planning principle. Athletes don't care about the number of people watching, just the roar of the crowd and the atmosphere. The Olympic Games are not awarded on the basis of who can build the biggest venue, they are judged on a city’s ability to deliver functional, sustainable and financially responsible infrastructure. In fact, recent Games have embraced smaller, right-sized venues to avoid white-elephant stadiums and crippling post-Games maintenance costs. Brisbane’s legacy will be judged far more on the smartness of its planning than the size of its grandstand.

Historic Olympic Cost Overruns

Hosting the Olympic Games has long proven to be a budgetary minefield. A landmark Oxford University study revealed that virtually no Games since 1960 have stayed within budget and cost overruns are the norm. In Seattle’s 1976 Summer Olympics, for instance, the overrun reached a staggering 720%, one of the most extreme in modern history.

Even more recent hosts have struggled. London’s 2012 Games overshot their projected budget by 76%, despite heavy public scrutiny and advanced planning.

As Consultant Professor Bent Flyvbjerg put it, the costs of hosting the Olympics are “comparable to ‘deep disasters’ like pandemics, earthquakes, tsunamis, and war.”

Given these historic patterns, opting for a budget-busting stadium at Victoria Park signals a financial disaster in the making.

The Economic Cost of a “White Elephant” Stadium

Since the stadium debate began, social media has been awash with calls from some AFL and cricket fans for a high volume seat stadium in Brisbane to rival other stadium locations like the MCG in Melbourne. However, there is little evidence to suggest that a venue of that scale is necessary or economically viable in Brisbane. In fact, global trends in stadium design are shifting away from oversized, rarely filled venues. Sporting authorities across Europe and the United States increasingly caution against the creation of “white elephant” stadiums - facilities that are expensive to build and maintain, but ultimately underutilised.

A review of the Gabba’s bookings between 7 July 2024 and 7 July 2025 shows it was booked for just 29 events, approximately 8% of available time. While that may align with certain event-based business models, the broader economic picture tells a different story. The ‘opportunity cost’ of replacing free, open green space with closed-off, ticketed concrete buildings must also be considered. This isn’t just about event revenue; it’s about what is lost to the wider community.

"Mega sporting events require short-term, exceptionally large investments in infrastructure, often resulting in costly stadiums that become ‘white elephants’ - structures that not only put a financial strain on cities but may become useless after the event."

- Sport and Dev, 2015

Instead, the future lies in smaller, smarter stadiums that prioritise atmosphere, flexibility and financial sustainability. This includes modular designs with retractable or temporary seating, and technology-enabled enhancements to improve the experience for fans watching remotely. In this context, GIICA’s insistence on a 60,000–65,000-seat benchmark stadium for Brisbane becomes increasingly difficult to justify, particularly when alternative sites like the Gabba were dismissed primarily on the basis of not meeting that arbitrary capacity target.

While it may be tempting to argue for a big, bold stadium to boost Brisbane’s image, the economic realities of constructing a venue that far exceeds the city’s actual needs are hard to ignore. Oversized stadiums often become costly “white elephants” rarely filled to capacity. The financial risks and long-term burden to the Queensland tax payers in building more seats than will be used for the vast majority of events are significant. Some of the key economic drawbacks of excess stadium capacity include -

Higher upfront construction costs: Larger stadiums require more materials, land preparation and engineering, significantly driving up initial capital expenditure for often marginal gains in capacity. Importantly, while upper-tier seating adds to construction complexity and cost, these ‘nosebleed seats’ typically generate lower ticket revenue, offering diminishing returns on investment.

Increased ongoing maintenance: Every additional seat adds to cleaning, repairs, security, lighting, staffing and compliance costs, regardless of whether or not it’s occupied during events.

Wasted operational expenses: Hosting events at underfilled venues results in disproportionate costs for utilities, transport, staffing and policing - without the revenue to match.

Depressed atmosphere and reduced fan experience: Empty sections create a visibly and audibly flat experience, impacting fan engagement and reducing return visitation.

Reduced profitability for smaller events: Smaller-scale games or concerts often avoid booking oversized stadiums because the optics and costs don’t suit their audience size.

White elephant risk: Large venues that are only filled for rare, marquee events (eg. opening ceremonies, finals) end up sitting idle or underused for most of the year, draining public funds.

Opportunity cost: Funding oversized stadiums ties up public money that could be invested in community-level infrastructure, health, education or grassroots sport.

Revenue shortfall projections: Overestimating attendance figures can result in financial models that never break even, let alone turn a profit, placing long-term burden on ratepayers or governments.